Physical AI refers to AI systems capable of perceiving, reasoning and acting in the physical world through real-time sensing, simulation-trained models and edge compute. Unlike digital agentic AI, Physical AI enables autonomous machines such as robots, AMRs and humanoids to operate reliably in factories, warehouses and logistics environments.

What Is Physical AI? Robotics, Perception and Industrial Edge AI Computing 2026-2030

Executive Key Takeaways

1. Physical AI moves AI from software into the physical world, enabling robots and machines to act autonomously in real environments.

2. NVIDIA’s three-computer architecture defines the stack: training (cloud), simulation (digital twins), deployment (edge), and perception (reality).

3. Models and simulation are maturing; the true bottleneck has shifted to perception — real-world sensing and edge inference.

4. The first commercial adoption waves will come from warehousing, factory automation, industrial inspection, digital twin factories and humanoid robots.

5. Physical AI is not a software revolution — it is an industrial systems revolution, with ROI driven by productivity, labor substitution, safety and 24/7 operations.

6. The industry conclusion is clear: Physical AI cannot scale until the perception layer and industrial supply chain scale.

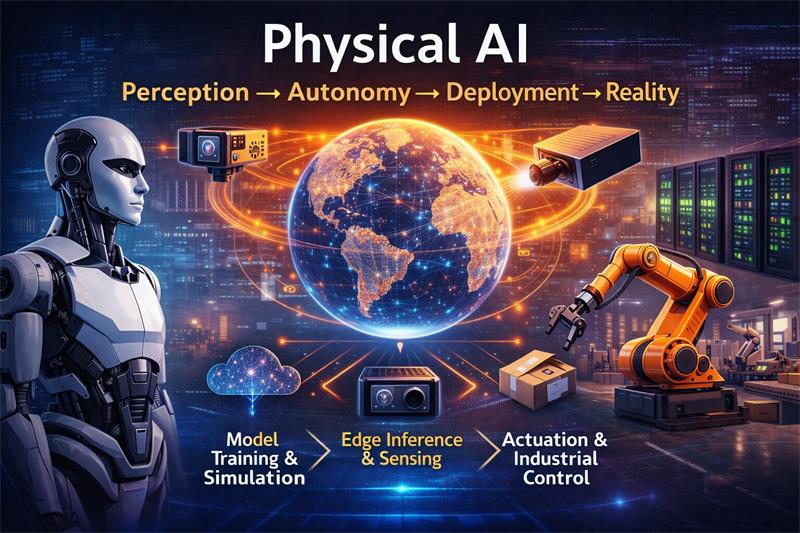

7. Winners will be those who master the full loop from perception → autonomy → execution, not those who only ship software.

The term Physical AI entered the mainstream at CES 2026, signaling a critical transition in the evolution of artificial intelligence. After a decade dominated by cloud inference, conversational models, and digital task automation, the frontier of AI has now shifted toward autonomous machines capable of acting safely and intelligently in the physical world — from humanoid robots and warehouse AMRs to factory automation, inspection systems and autonomous mobility.

During his CES 2026 keynote, NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang described the moment succinctly:

“The ChatGPT moment for robotics is here. Breakthroughs in physical AI — models that understand the real world, reason and plan actions — are unlocking entirely new applications.”

This framing marks a departure from the paradigm that defined generative AI. In the world of text, media and digital workflows, latency, uncertainty, safety envelopes and environmental complexity are manageable. But in the physical world, AI must operate under tightly constrained realities — a robot must process sensory data, form world models, understand context, plan trajectories and actuate hardware, often in milliseconds. Failure is not a formatting error; failure can mean collisions, downtime, or accidents.

Jensen Huang further clarified how NVIDIA differentiates the new category:

“Physical AI enables autonomous systems to perceive, understand, reason and perform or orchestrate complex actions in the physical world.”

While generative AI and agentic AI captured attention by transforming software interactions, Physical AI extends intelligence beyond screens and APIs, into factories, warehouses, logistics hubs, hospitals, construction sites and urban environments. The concept is inherently multidisciplinary — combining robotics, machine vision, mechanical actuation, edge computing, digital twins, simulation, and human-in-the-loop safety.

Critically, Physical AI also introduces new commercial dynamics. The first wave of AI primarily disrupted software categories — productivity tools, marketing, customer service, coding, and media. In contrast, the Physical AI wave is poised to disrupt industries with atoms, not just bits: manufacturing, logistics, defense, infrastructure, autonomous mobility and industrial automation. These sectors represent multi-trillion-dollar supply chains and long-term capital deployment cycles, with procurement led by CTOs, COOs, heads of automation and C-level industrial buyers rather than IT managers.

NVIDIA did not present Physical AI as a marketing slogan, but as a distinct category of AI with new technical requirements, new deployment models, and new economic implications. More importantly, the company provided a clear definition and positioned it within a coherent technology stack.

During CES 2026, Jensen Huang explained the conceptual leap directly:

“Robotics, which has been enabled by physical AI — AI that understands the physical world. It understands things like friction and inertia, cause and effect, object permanence… it’s still there, just not seeable.”

This sentence articulates why Physical AI diverges from generative AI and digital agentic AI. Understanding the physical world is not merely a matter of perception — it requires an internal model of dynamics and consequence. A robot must understand that liquids spill, boxes deform, floors can be slippery, objects occlude each other, lights change over time and humans move unpredictably. These real-world variables introduce uncertainty that purely digital AI does not face.

NVIDIA’s official definition solidifies this distinction:

“Physical AI enables autonomous systems to perceive, understand, reason and perform or orchestrate complex actions in the physical world.”

The company further contrasts Physical AI with agentic AI:

“Unlike agentic AI, which operates in digital environments, physical AI are end-to-end models that can perceive, reason, interact with and navigate the physical world.”

This framing has several strategic implications for industries now evaluating Physical AI:

Unlike cloud-based LLMs, these systems must operate within constraints such as:

These constraints shift the compute locus from cloud → edge → physical devices.

NVIDIA emphasized that Physical AI relies on multi-modal foundation models trained on:

This aligns with the emerging robotics consensus that robots will need models that unify perception, language, world-knowledge and action — an evolution beyond LLMs and diffusion models.

Generative models produce outputs; physical models must produce behavior.

NVIDIA noted that Physical AI models enable systems that can:

This is why Jensen Huang stated:

“We’re entering the era of physical AI.”

The phrasing is deliberate: not “we will enter,” but “we are entering”, implying the category has crossed from research into early commercialization.

One of the most consequential ideas NVIDIA introduced at CES 2026 was that Physical AI requires an entirely new computing architecture — one that spans from data centers to digital twins to the machines operating in factories and warehouses. Jensen Huang described this as a “three-computer architecture”, each layer serving a distinct function in the Physical AI pipeline.

During CES, Jensen Huang explained:

“A three-computer architecture — data center training, physically accurate simulation, and on-device inference — is becoming the operating system for physical AI.”

This framing is powerful because it positions Physical AI not as a monolithic model running on a robot, but as a distributed system:

The first computer trains multi-modal, robotics-focused foundation models capable of understanding:

These models consume massive datasets drawn from real robots, synthetic digital twins, teleoperation, simulation and video. Jensen Huang noted that these models can be trained to “understand space and motion,” enabling transfer between simulated and real-world environments.

The second computer simulates the physical world with sufficient fidelity to train and validate Physical AI models safely and cost-effectively. NVIDIA emphasized that digital twins and simulation are training infrastructure, not visualization tools. As Jensen Huang explained:

“Omniverse enables physically accurate simulation and synthetic data generation to reduce the sim-to-real gap in robotics and autonomous systems.”

Digital twins allow for:

Simulation is critical because running these scenarios in real factories or warehouses would be impractical, unsafe or uneconomical.

The third computer executes Physical AI models on machines deployed in the field. These include:

During CES, Jensen Huang highlighted that NVIDIA Jetson Thor was designed “for the new era of autonomous machines powered by physical AI.” However, the ecosystem extends beyond Thor; current deployments are actively utilizing NVIDIA Jetson Orin AGX, Orin Nano, and Xavier NX to handle the immediate inference workloads of 2026

This layer must satisfy constraints generative AI largely ignored:

Collectively, these three computers form the operating system for Physical AI, linking cloud intelligence, digital rehearsal and real-world execution.

While simulation and digital twins represent major breakthroughs, NVIDIA made it clear that Physical AI faces a fundamental challenge: the real world is not a controlled environment, and machines must operate safely amid uncertainty, variability and incomplete information.

In robotics research, this is known as the simulation-to-reality gap — or sim-to-real gap.

NVIDIA acknowledged this challenge explicitly, noting that real-world deployment introduces conditions that are difficult to model:

“Physical AI introduces uncertainty — surfaces are slippery, objects are deformable, lighting changes, sensors are noisy and environments are unstructured.”

These uncertainties manifest across several domains:

Simulation cannot perfectly replicate:

For robots, these factors impact path planning, grasping, manipulation and locomotion.

Factories, warehouses and construction sites introduce variability that differs from digital environments:

This is why digital-native agentic AI cannot be deployed directly into industrial spaces.

Physical AI requires real-world sensing from:

However, sensors introduce:

These distortions require models robust enough to generalize beyond perfect synthetic data.

Unlike cloud-based AI, Physical AI must close the loop between:

perception → planning → control → actuation

in extremely tight latency windows. Failure is not cosmetic — it impacts safety, uptime, quality and liability. For example:

Downtime costs can exceed software errors by orders of magnitude.

To mitigate the sim-to-real gap, NVIDIA is investing heavily in:

These techniques allow Physical AI models to rehearse millions of scenarios safely before deployment.

But as NVIDIA implicitly acknowledged during CES: simulation alone is insufficient. Real-world sensing and perception remain indispensable for grounding models in physical reality.

The central insight emerging from CES 2026 is that the limiting factor for Physical AI is no longer model size, simulation fidelity or GPU throughput — it is perception.

Physical AI systems must operate autonomously in real-world environments. To do so safely and profitably they must first see, then understand, then decide, and finally act. The entire stack fails if perception fails at the input layer.

During CES, Jensen Huang emphasized the expanded role of perception in robotics and automation, noting that AI-powered machines must now “understand the physical, three-dimensional world” rather than simply process digital abstractions.

For Physical AI, perception introduces a new set of requirements that generative AI did not confront:

Without sensors, a robot has no grounding. It has no world model, no object permanence, no affordances and no spatial awareness. In robotics, this is not an intellectual abstraction — it is a blocking constraint.

The control logic is simple:

No sensing → No perception → No world model → No planning → No control → No action

It is not possible to skip or fake these layers via cloud inference.

Unlike LLM inference or diffusion media generation, Physical AI cannot afford cloud round-trips. Factories, warehouses and autonomous systems require:

The edge, not the cloud, becomes the default execution venue for Physical AI.

This is why NVIDIA designed Jetson Thor specifically “for the new era of autonomous machines powered by physical AI.”

While robotics can incorporate lidar, radar, IMU and ultrasonic sensors, cameras provide unmatched data density and multimodal grounding:

These attributes cannot be replaced by scalar sensors. Cameras allow robots to interpret not just where objects are, but what they are, how they behave and what actions are possible.

This is why robotics research increasingly incorporates vision-language-action models and robotic foundation models, trained jointly on:

The trend is especially pronounced in:

As Physical AI moves out of the lab and into revenue-bearing deployment, perception is maturing from a component into infrastructure. OEMs, integrators and industrial end-users increasingly need:

This is where the Physical AI market diverges sharply from the cloud AI market: atoms matter, thermal envelopes matter, and hardware matters.

The promise of Physical AI becomes clearest not in research labs, but in commercial deployment environments where labor, safety, productivity and uptime define economic outcomes. While generative AI disrupted digital workflows, Physical AI targets sectors where automation has been constrained by physical complexity rather than software availability.

During CES, Jensen Huang emphasized this shift toward real-world industries:

“AI is transforming the world’s factories into intelligent thinking machines — the engines of a new industrial revolution.”

Six major application domains have emerged as early adopters of Physical AI:

Warehouses represent one of the highest-likelihood deployment arenas for Physical AI due to:

AMRs (Autonomous Mobile Robots) are already scaling across logistics hubs, cross-docks, parcel sorting centers and distribution centers. These robots depend on robust computer vision, spatial perception and edge inference to navigate mixed human-machine environments at high uptime rates.

The warehouse automation market is projected to grow at double-digit CAGR into the 2030s as Physical AI unlocks more dynamic operations beyond structured pallet racking.

Factories are transitioning from fixed, pre-programmed automation to flexible, adaptive automation enabled by Physical AI. Tasks such as:

require perception-driven manipulation rather than pure motion control.

Industrial buyers care less about “AI accuracy” than about cycle time, yield, defect rates, rework costs and compliance with quality systems, all of which impact total manufacturing cost and ROIC (Return on Invested Capital).

Digital twins enable manufacturers to rehearse process changes, analyze production constraints, optimize layouts and validate robotics deployments without interrupting production.

However, these twins only become valuable when synchronized through real-world perception, creating a continuous loop:

Digital Twin ↔ Physical Factory ↔ Perception Layer

This loop increases uptime, reduces unplanned downtime and lowers integration risk.

Humanoid robots entered the Physical AI narrative as Jensen Huang framed them as one of three major form factors alongside autonomous vehicles and agentic robots.

Key drivers include:

These robots require high-bandwidth visual sensing, especially in hand-eye coordination, grasping, and manipulation tasks.

Outdoor and semi-structured environments introduce high perception complexity due to:

Physical AI allows last-meter logistics systems (e.g., sidewalk delivery robots, autonomous tuggers, automated carts) to operate more safely and reliably.

FAQ Q: Where are the biggest supply chain opportunities in Physical AI?

A: Contrary to popular belief, the biggest opportunities are not in GPUs or foundation models — those are already firm. The emerging gaps are in:

In Physical AI, the world starts at the sensor, and the sensor is becoming the limiting factor for autonomy scale-out.